Cultural Currents: First Nations Underwater Cultural Heritage and Offshore Wind Development

The rich cultural history of First Australians is deeply intertwined with Australia’s natural landscapes, both on land and beneath the sea. First Nations people have a profound connection to the oceans and seas, and this connection is echoed in the presence of underwater heritage sites that hold invaluable cultural, historical, and spiritual heritage. For thousands of years, coastal oceans provided a vast and varied food source for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Prior to significant sea level rise, much of Australia’s now shallow coast was once dry land, home to thousands of generations of First Nations people. As the offshore wind sector continues to gain momentum in Australia, it is crucial to understand and address the potential impact of these developments on submerged landscapes and potentially culturally significant sites.

What are First Nations Underwater Heritage Sites?

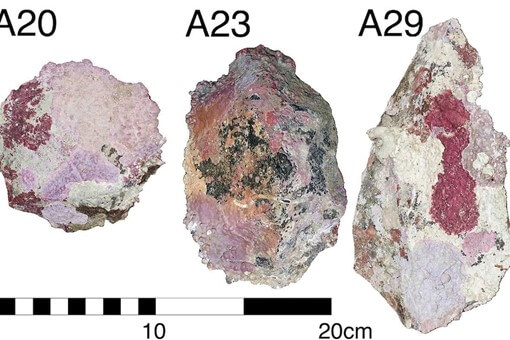

The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage defines Underwater Cultural Heritage as ‘…traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally under water, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years.’ In the context of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, examples can include coastal shell middens, stone fish traps and weirs, rock art, and sunken indigenous artifacts, such as tools and weapons. In 2019, 14 metres underwater off the Murujuga coastline in Western Australia, researchers from Flinders University uncovered 269 ancient stone tools and grinding stones. Using the depth of the site as an indicator, the researchers estimated it to be roughly 9000 years old. This example is distinct proof of a previous settlement in this now sunken region.

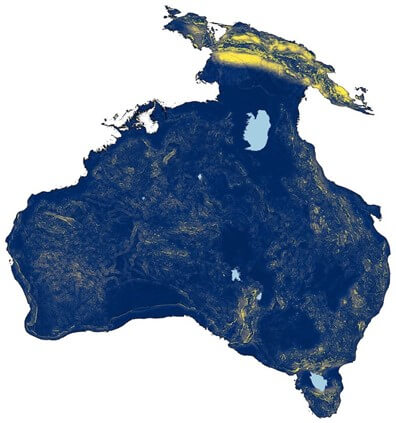

Unfortunately, there haven’t been many underwater discoveries in Australia, which is most likely due to a lack of sufficient investigation. One reason for this may be that a vast area of Australia’s continental shelf (2 million square kilometres) has been lost to rising seas in the last 20,000 years. This amounts to more than a quarter of Australia’s current land area. From the time the first people in Australia arrived, more than 65,000 years ago, these vast swathes of land have been dry and inhabitable for significantly longer than they have been underwater, and thus are almost certain to be rich in cultural history.

If efforts are taken to learn more about these significant cultural sites, they can serve as repositories of traditional knowledge and provide insights into practices that have sustained indigenous cultures for millennia. Moreover, these sites have the potential to promote cultural awareness and understanding among broader society.

Minimising Impacts on Underwater Heritage Sites from Offshore Wind Development:

Offshore wind development is a complex and multi-faceted process that involves careful planning, environmental assessment, and stakeholder engagement, to minimize various potential impacts. While the impacts of these projects on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are generally associated with onshore works, it is important to consider the potential offshore impacts on Underwater Cultural Heritage Sites. Most of these Heritage Sites are believed to be at a depth of 30-70 metres below the sea, as this was the depth of the Australian coastline between 65,000 and 30,000 years ago. This is very similar to the range of water depths that many offshore wind developers will be looking at for fixed foundation turbine projects in Australia, that are feasible in depths of up to 60 metres.

The Australian Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (Underwater Heritage Act) currently protects shipwrecks and sunken aircraft aged more than 75 years, as well as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Underwater Cultural Heritage in Commonwealth waters. The Federal Government has recently released draft guidelines for offshore work to protect Underwater Cultural Heritage. These guidelines include key recommendations, such as early engagement with First Nations groups and utilising specific methods for identifying and assessing First Nations Underwater Cultural Heritage. These guidelines are expected to be released in late 2023 and are likely to be followed by legislative reforms. To minimize the impact that offshore wind farms have on First Nations Underwater Heritage Sites, developers should work in a collaborative and open manner with Indigenous communities and Government bodies during this reform process, and during the planning and implementation of any offshore wind project.

Conclusion:

While they remain mostly undiscovered, Australia’s First Nations underwater heritage sites are invaluable treasures that offer a unique look into our country’s Indigenous cultures and histories. There is a clear need in Australia for the development of new renewable energy projects such as offshore wind. However, the planning and development of projects must be undertaken in a collaborative manner with traditional owners to avoid and minimise impacts to significant sites.

By implementing collaborative planning, consultation, and mitigation strategies, Australia can move toward a future where renewable energy coexists harmoniously with the rich cultural heritage beneath the waves. Preserving these underwater sites is not only a legal and ethical responsibility, but it is also a testament to the nation’s commitment to respecting and celebrating the diverse heritage that has shaped its identity.

Interested in working with Energise Renewables?